Monday, 15 June 2015

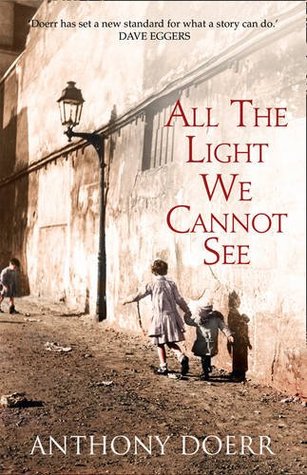

Review and Thoughts on: All The Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

I had heard only good things about All The Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr, so when I picked it up from the library I was excited to read it. It is a large book, and something of a slow read. I would categorise it as historical literary fiction, it is set in World War Two, and is exquisitely written. The chapters are short, sometimes only a page, but each are intimately detailed, depicting the stories of of two children who grow up during the war. The narrative moves between the end of the war, and the events that lead the characters to that point, starting from the first rumblings of Nazi Germany. It also switches perspectives, primarily telling the stories of Marie-Laure, a blind French girl, and Werner, a German orphan.

I found Marie-Laure a captivating character, and the chapters about her deeply engaging. However, switching to Werner was a jarring feeling. I didn't feel I empathised with him as much, it seemed more of an observational experience while Marie-Laure's story was immersive. Marie-Laure provides an unusual perspective of occupied France, the people in the town's acts of resistance as well as her experiences of the losses that war brought, and I connected with her. While Werner provides a perspective of the poverty and propaganda that provided a foundation for Hitler, as well as the experiences within the Nazi army and the cost of their power and then defeat.

The supportive characters, such as Marie-Laure's father, her great-uncle and Madame Manec were well-characterised and their relationships provided a wonderful depth to the story. Similarly, I appreciated characters such as Fredrick, Jutta and Volkheimer in Werner's story, but often felt I cared more for them than Werner.

Though perhaps most of the worst aspects of what occurred in the story were in Werner's experiences of the war, and I certainly felt sad that these experiences happened, I was most emotional in Marie-Laure's early chapters, her innocence, confusion and reliance on her father who can only make false promises of security to her, and the change that brings in her in heart-breaking.

All The Light We Cannot See is a very well crafted story, and can be enjoyed simply as a wonderful use of language and expression. It is also deeply thought provoking, a story that must be absorbed and cannot be read quickly. Through detailed, beautiful imagery and characterisation the story examines themes such as innocence, suffering, courage, and the choices people must make. It is worth reading for the writing alone, but I also appreciated the thoughts it sparked.

A small incoherent ramble:

I spent sometime in the evening after finishing the novel thinking about the narrative of war, and in particular the kinds of stories about war we read. It occurred to me that most of the fictionalised accounts of World War Two that I have read mention of the atrocities committed in concentration camps, but are rarely from that perspective (example, The Book Thief, it certainly contains information about the persecution of Jewish people, but it is focused on the challenge of German citizens). And often challenge the idea of glorifying war, by talking of the suffering of soldiers, and even of civilians. They will challenge the propaganda idea of the all-good allies and all evil Nazis. Is it easier to remember the humanity of the German people (something I think is deeply important) without that perspective of their very worst actions? Is it because if we humanise those who stood by, or those who fought on the loosing side it reminds us that we are also capably of great atrocities. Is the Holocaust too horrific? Is it easier to talk of the horrors of war than of the state-sanctioned systematic genocide? Is it because we don't want to acknowledge we still Other Jewish people, or any of the other groups persecuted by Nazi Germany?

I am not saying there are not stories that do this, and I have read some stories written by Jewish survivors. However, it does seem to me the talked about books, the celebrated books, are more like The Book Thief or All The Light We Cannot See and I think this is dangerous, particularly given the obvious continuation of anti-Semitism throughout the western world (there also broader implications such as the extremely worrying trend towards indefinite detention for refugees - lead by Australia - which I think has similarities but don't want to take away from the specificity of the Holocaust).

I don't have answers, but this is something I want to think more about, and so I am glad I read this book, which challenged this thought process.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)